Cystine Bladder Stones in Dogs

My dog has cystine bladder stones. What are they?

Bladder stones (uroliths or cystic calculi) are rock-like formations of minerals that form in the urinary bladder, and are more common than kidney stones in dogs. A somewhat rare form of urolith in the dog is composed of cystine crystals.

How did my dog develop cystine bladder stones?

Cystine bladder stones appear to be the result of a genetic abnormality that prevents a dog from reabsorbing cystine from the kidneys. This condition is believed to be inherited in dogs.

How common are cystine bladder stones?

While bladder stones in general are somewhat common in dogs, cystine bladder stones are rare. Cystine uroliths are most commonly diagnosed in male dogs (98% of dogs diagnosed with cystine bladder stones are male).

What are the signs of cystine bladder stones?

The signs of bladder stones are very similar to the signs of an uncomplicated bladder infection or cystitis. The most common signs that a dog has bladder stones are hematuria (blood in the urine) and dysuria (straining to urinate). Hematuria occurs because the stones rub against the bladder wall, irritating and damaging the tissue and causing bleeding.

Dysuria may result from inflammation and swelling of the bladder walls or the urethra (the tube that transports the urine from the bladder to the outside of the body), from muscle spasms, or from a physical obstruction to urine flow caused by the presence of the stones. Veterinarians assume that the condition is painful, because people with bladder stones experience pain, and because many clients remark about how much better and more active their dog becomes following surgical removal of bladder stones.

"A complete obstruction is potentially life threatening and requires immediate emergency treatment."

Large stones may act almost like a valve or stopcock, causing an intermittent or partial obstruction at the neck of the bladder, the point where the bladder attaches to the urethra. Small stones may flow with the urine into the urethra where they can become lodged and cause an obstruction. If an obstruction occurs, the bladder cannot be emptied fully; if the obstruction is complete, the dog will be unable to urinate at all. If the obstruction is not relieved, the bladder may rupture. A complete obstruction is potentially life threatening and requires immediate emergency treatment.

How are cystine bladder stones diagnosed?

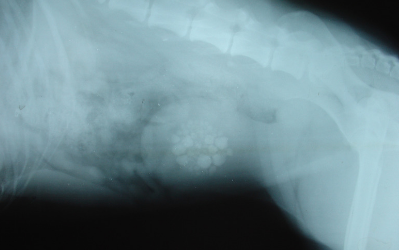

In some cases, as long as the dog is relaxed and the bladder is not too painful, your veterinarian may be able to palpate (feel) cystine bladder stones in the bladder. However, some cystine bladder stones are too small to detect by palpation. Unfortunately, many cystine stones are radiolucent, meaning they are not visible on radiographs (X-rays). This means that your veterinarian may need to perform other imaging studies such as a bladder ultrasound or a contrast radiographic study, a specialized technique that uses dye to outline the stones in the bladder.

(Image via Wikimedia Commons / Joel Mills (CC BY-SA 3.0.)

If your veterinarian suspects that your dog has cystine bladder stones based on breed, clinical signs, and results of a urinalysis, one or both of these specialized imaging techniques may be recommended.

"The only way to be certain that a particular bladder stone is a cystine bladder stone is to have it analyzed at a veterinary diagnostic laboratory."

The only way to be certain that a particular bladder stone is a cystine bladder stone is to have it analyzed at a veterinary diagnostic laboratory. In some cases, your veterinarian may make a presumptive diagnosis about the type of stone that is present based on the findings on imaging studies and results of a urinalysis. For example, if your dog is one of the breeds predisposed to this type of stone, if ultrasound or contrast X-rays show that there are one or more stones present in the bladder, and if the results of the urinalysis show the presence numerous cystine crystals, your veterinarian may make a presumptive diagnosis of cystine bladder stones and start treatment accordingly.

How are cystine bladder stones treated?

There are two primary treatment strategies for treating cystine bladder stones in dogs: non-surgical removal called urohydropropulsion and surgical removal.

In selected cases, small stones may be removed non-surgically by urohydropropulsion. In simplest terms, the bladder stones are flushed out of the bladder using a special urinary catheter technique. This is only possible when the stones are very small in diameter. If your veterinarian has a cystoscope, small stones in the bladder can sometimes be removed with this instrument, therefore avoiding the need for surgery to open the bladder. Sometimes these procedures may be performed with your dog under heavy sedation, although general anesthesia is often necessary. Either of these non-surgical procedures may be used to obtain a sample stone for analysis so that your veterinarian can determine if dietary dissolution is feasible.

Surgical removal is commonly recommended in cases where the bladder stones are too large for urohydropropulsion, when there are a large number of stones present in the bladder, or if there is an increased risk of urinary obstruction. This is also the quickest way of treating bladder stones; however, it may not be the best option for patients that have other health concerns, or in whom general anesthesia could be risky. With this option, the stones are removed via cystotomy, which means that the bladder is surgically exposed and opened so that the stones can be removed. This routine surgery is performed by many veterinarians and dogs usually make a rapid post-operative recovery. If the stones have obstructed the urethra, so that the dog is unable to urinate, an emergency surgery must be performed IMMEDIATELY to save the dog's life.

Your veterinarian will discuss the pros and cons of each of these options with you and help you decide which option is best in your situation.

Your veterinarian will discuss the pros and cons of each of these options with you and help you decide which option is best in your situation.

Are there any other treatment options?

In some selected referral centers, another option may be available to treat bladder stones. This option is ultrasonic dissolution, a technique in which high frequency ultrasound waves are used to disrupt or break the stones into tiny particles that can then be flushed out of the bladder. It has the advantage of immediate removal of the offending stones without the need for surgery. Your veterinarian will discuss this treatment option with you if it is available in your area.

My dog is not showing any signs. What will happen if I do nothing?

In cases where only a few small bladder stones are present and the dog is not experiencing clinical signs (painful or frequent urination, blood in the urine, etc.), it might seem reasonable to do nothing. The most common scenario for this situation is when bladder stones are found as an 'incidental' finding when an X-ray is performed for another reason. Since cystine bladder stones virtually always occur in male dogs, and male dogs are at an increased risk of urinary obstruction due to a small stone becoming lodged in the urethra, it can be extremely risky to adopt a wait-and-see approach.

However, if for some reason the patient cannot undergo surgical treatment or non-surgical stone removal, and you are willing to assume the risks, it may be acceptable to delay the treatment for a short while. During this time the diet is often changed to one less likely to contribute to cystine stone formation. However, if there is ANY indication that your dog's condition is worsening, or if the dog develops a urinary obstruction, you must seek immediate veterinary attention.

How can I prevent my dog from developing cystine bladder stones in the future?

Dogs that have developed cystine bladder stones in the past will often be fed a therapeutic diet for life (see handout “Nutritional Concerns for Dogs with Bladder Stones” for more information). Diets that promote alkaline urine that is more dilute are recommended. Most dogs should be fed a canned or wet diet to encourage water consumption. Dilute urine with a low urine specific gravity (USpG less than 1.020) is an important part of the prevention of cystine bladder stones. In certain cases, medications such as n-(mercaptopropionyl)-glycine (2-MPG) (Thiol) may be required. Urinary alkalinizers (e.g., potassium citrate) may be needed to maintain an alkaline urine pH of greater than 7.5.

"Dogs displaying any clinical signs such as frequent urination, urinating in unusual places, painful urination or the presence of blood in the urine should be evaluated immediately."

In addition, careful routine monitoring of the urine to detect any signs of bacterial infection is also recommended. Bladder X-rays and urinalysis will typically be performed one month after treatment and then every three to six months for life. Dogs displaying any clinical signs such as frequent urination, urinating in unusual places, painful urination or the presence of blood in the urine should be evaluated immediately. Unfortunately, cystine stones have a high rate of recurrence, despite careful attention to diet and lifestyle.